For a video version of this tutorial, click here.

This vignette introduces key terminology and walks you through

setting up a simple pipeline using rixpress.

Understanding the concepts presented here is helpful but not mandatory.

I recommend reading through this vignette, but don’t worry if you don’t

grasp everything immediately. You can try building a simple pipeline by

following the next vignette, vignette("b-core-functions"),

and then return to this one; things should become clearer after some

hands-on experience!

Also, this package makes heavy use of its sister package

rix, and I highly recommend that you first get familiar

with Nix by using rix. With

rix, you’ll learn how to set up reproducible development

environments for data science, which you can use for interactive data

analysis work. Then, if you want to go one step further in the reproducibility

spectrum/continuum, this is where rixpress comes

in.

Definitions

In Nix terminology, a derivation is a specification

for running an executable on precisely defined input files to repeatably

produce output files at uniquely determined file system paths. (source)

In simpler terms, a derivation is a recipe with precisely defined inputs, steps, and a fixed output. This means that given identical inputs and build steps, the exact same output will always be produced. To achieve this level of reproducibility, several important measures must be taken:

- All inputs to a derivation must be explicitly declared.

- Inputs include not just data files, but also software dependencies, configuration flags, and environment variables, essentially anything necessary for the build process.

- The build process takes place in a hermetic sandbox to ensure the exact same output is always produced.

The next sections of this document explain these three points in more detail.

Derivations

Here is an example of a simple Nix

expression:

let

pkgs = import (fetchTarball "https://github.com/rstats-on-nix/nixpkgs/archive/2025-04-11.tar.gz") {};

in

pkgs.stdenv.mkDerivation {

name = "filtered_mtcars";

buildInputs = [ pkgs.gawk ];

dontUnpack = true;

src = ./mtcars.csv;

installPhase = ''

mkdir -p $out

awk -F',' 'NR==1 || $9=="1" { print }' $src > $out/filtered.csv

'';

}I won’t go into details here, but what’s important is that this code

uses awk, a common Unix data processing tool, to filter the

mtcars.csv file to keep only rows where the 9th column (the

am column) equals 1. As you can see, a significant amount

of boilerplate code is required to perform this simple operation.

However, this approach is completely reproducible: the dependencies are

declared and pinned to a specific dated branch of our

rstats-on-nix/nixpkgs fork, and the only thing that could

make this pipeline fail (though it’s a bit of a stretch to call this a

pipeline) is if the mtcars.csv file is not

provided to it.

You could then add another step that uses filtered.csv

as input and continue processing it. If you label the above code as

f and a subsequent chunk of Nix code as

g, then adding another step would essentially result in the

following computation: mtcars |> f |> g, where

f and g are pure functions, and the pipeline

is thus a composition of pure functions.

Nix builds filtered.csv in two steps: it

first generates a derivation from this expression, and only

then builds it. For clarity in this document, I’ll refer to code like

the example above as a derivation rather than an expression, to

avoid confusion with the concept of expression in R.

The goal of rixpress is to help you write pipelines

like mtcars |> f |> g without needing to learn

Nix, while still benefiting from its powerful

reproducibility features.

Dependencies of derivations

Nix requires the dependencies of any derivation to be

explicitly listed and managed by Nix itself. If you’re

building output that requires, for example, Quarto, then Quarto must be

explicitly listed as an input, even if you already have Quarto installed

on your system. The same applies to Quarto’s dependencies, and all the

dependencies of those dependencies, all the way down to the common

ancestor of all packages. With Nix, to run a linear

regression with R, you essentially need to build the entire universe of

dependencies first.

In Nix terms, this complete set of packages and their

dependencies are what its author, Eelco Dolstra, refers to as

component closures:

The idea is to always deploy component closures: if we deploy a component, then we must also deploy its dependencies, their dependencies, and so on. That is, we must always deploy a set of components that is closed under the ‘’depends on’’ relation. Since closures are self-contained, they are the units of complete software deployment. After all, if a set of components is not closed, it is not safe to deploy, since using them might cause other components to be referenced that are missing on the target system.

(Nix: A Safe and Policy-Free System for Software Deployment, Dolstra et al., 2004).

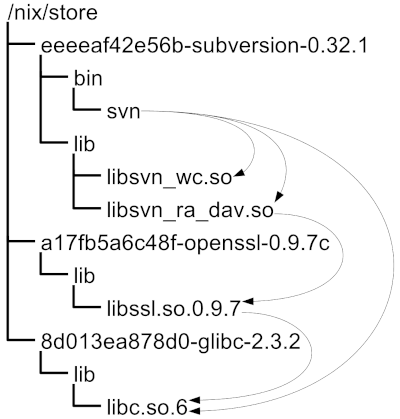

The figure below, from the same paper, illustrates this idea:

In the figure, subversion depends on

openssl, which itself depends on glibc.

Similarly, if you write a derivation that builds a data frame by

filtering mtcars, this derivation requires:

- An input file, such as

mtcars.csv. - R and potentially R packages like dplyr.

- All of R’s dependencies and the dependencies of any R packages.

- The dependencies of those dependencies (all the way down).

All of these must be managed by Nix. If any dependency

exists “outside” this component closure and is only available on your

machine, then the pipeline will only work on your machine -

defeating the purpose of reproducibility! (It should be noted, however,

that there are sometimes good reasons to have a dependency that is not

managed by Nix, in which case you might prefer to use

targets running inside a Nix shell instead of

rixpress, but these situations should be the exception

rather than the rule).

Nix distinguishes between different types of

dependencies (buildInputs, nativeBuildInputs,

propagatedBuildInputs,

propagatedNativeBuildInputs), but let’s skip this concept,

which is only relevant for packaging upstream software, not for defining

our pipelines. But if you’re curious, read this.

The Nix store and hermetic builds

When building derivations, their outputs are saved into the Nix

store. Typically located at /nix/store/, this folder

contains all the software and build artifacts produced by

Nix.

For example, if you write a derivation that computes the tail of a

file named mtcars.csv, once the derivation is built, its

output would be stored at a path like

/nix/store/81k4s9q652jlka0c36khpscnmr8wk7jb-mtcars_tail.

The long cryptographic hash uniquely identifies the build output and is

computed based on the content of the derivation along with all its

inputs and dependencies. This ensures that the build is fully

reproducible.

As a result, building the same derivation on two different machines will yield the same cryptographic hash, and you can substitute the built artifact with the derivation that generates it one-to-one. This is analogous to mathematics: if you consider the function , then writing or represents the same value.

This mechanism is what makes it possible to import and export build

artifacts between pipelines to avoid having to rebuild everything from

scratch on different machines or on continuous integration platforms.

rixpress has two functions that allow this, called

export_nix_archive() and

import_nix_archive().

To ensure that building derivations always produces exactly the same outputs, builds must occur in an isolated environment, often referred to as a sandbox. This approach, known as a hermetic build process, ensures that the build is unaffected by external factors or the state of the host system.

This isolation extends to environment variables as well. For example,

R users might set the variable JAVA_HOME to make R aware of

where the Java runtime is installed. However, if Java is required for a

derivation, setting JAVA_HOME outside of the sandbox has no

effect; it must be explicitly set within the sandbox. This isolation

also means that if you need to access an API to download data, it won’t

work because no internet connection is allowed from within the build

sandbox.

This may seem very restrictive, but it makes perfect sense if your

goal is to achieve complete reproducibility. Consider a scenario where

you need to use a function f() to access an API to get data

for your analysis. What guarantee do you have that running

f() today will yield the same result as running

f() in six months or a year? Will the API even still be

online?

For true reproducibility, you should obtain the data from the API once, then version and archive it, and continue using this archived data for your analysis (and share it with anyone who might want to reproduce your study).

Summary and conclusion

As explained at the beginning of this vignette, Nix

generates a derivation from a Nix expression through a

process called instantiation. Writing a reproducible pipeline with

Nix directly would require writing very long and complex

Nix expressions. This is where rixpress

comes in - it handles this complexity for you.

During instantiation, Nix processes your declarations,

resolves all inputs (including source files, build scripts, and external

dependencies), and computes a unique cryptographic hash. This hash is

derived from both the contents of your derivation and its entire

dependency graph, forming part of the derivation’s identity. This

ensures that even the smallest change in your inputs will result in a

distinct derivation, guaranteeing reproducibility. To avoid confusion

with the concept of expression in R, throughout this documentation I

refer to Nix expressions as derivations.

Once instantiated, derivations can be built. During the build

process, Nix constructs an isolated, hermetic environment

where only the explicitly declared dependencies are available. This

makes the build entirely deterministic, meaning that identical inputs

always produce identical outputs, regardless of the machine or

environment. This isolation improves reliability and facilitates

debugging and maintenance by eliminating external variables.

After a successful build, Nix stores the output in the

Nix store (typically at /nix/store/). For

example, if you build a derivation that processes the

mtcars.csv file, the output might be saved under a unique

path like

/nix/store/81k4s9q652jlka0c36khpscnmr8wk7jb-mtcars_tail.

The cryptographic hash is computed based on the derivation’s inputs and

build process. If anything changes, the hash will be different.

This is extremely precise - even changing the separator in the

mtcars.csv data set from , to |

will result in a different hash, even though the resulting

mtcars_tail object might look identical to us. From

Nix’s perspective, they’re different because one of the

inputs was different.

The key takeaway is that Nix is a complex tool because

it solves a complex problem: ensuring complete reproducibility across

different environments and time. rixpress and

rix are packages designed to make Nix more

accessible to R users, allowing you to benefit from Nix’s

reproducibility without having to learn all its complexities.

Now that you’re familiar with the basic Nix concepts,

let’s move on to the next vignette where you’ll set up your first basic

pipeline: vignette("b-core-functions").